Psychology & Cinema Series: The Parallax View

Welcome back to the Obscured Mirror!

Today’s post continues our series on psychology in film, where I explore movies with strong psychological themes, films I’ve discussed in class, sometimes even used for extra credit assignments, and always found worth revisiting for what they reveal about the human mind.

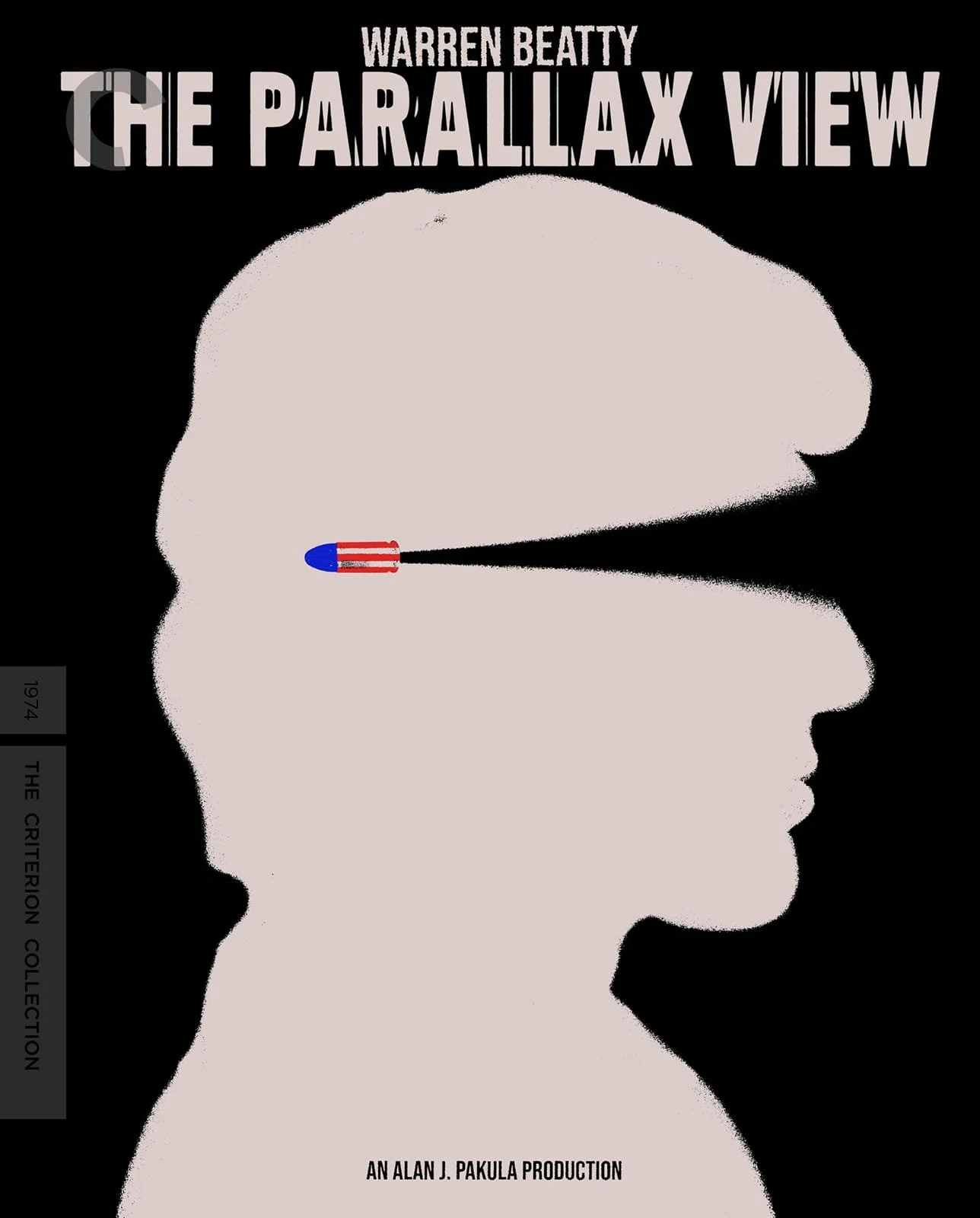

The film I want to focus on today is The Parallax View (1974), based on Loren Singer’s 1970 novel of the same name. Directed by Alan J. Pakula and starring Warren Beatty, it is a deeply unsettling political thriller that grew out of the paranoia and disillusionment of the 1970s. This was a bleak, cynical period in American history: Vietnam had divided the country, Watergate eroded public trust, and the lingering trauma of political assassinations (John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X) left Americans wondering if democracy itself was stable.

But The Parallax View is not just a time capsule of 1970s fear. The themes it wrestles with, corporate power, conspiracy, and the psychology of violence, remain disturbingly relevant today. In fact, watching the movie today, I think we can feel its shadow stretching across decades of political thrillers and conspiracy narratives that followed.

Before diving into the psychological angle, though, let me give you the basics. And, yes, a spoiler warning: if you want to experience the movie’s suspense and twists firsthand, pause here and go watch it.

The Story: Lone Gunmen and Hidden Puppeteers

Warren Beatty plays Joe Frady, a charismatic investigative journalist who stumbles into a conspiracy after a U.S. senator is assassinated. Frady discovers that witnesses connected to the assassination are dying under mysterious circumstances. His pursuit of the truth leads him to the shadowy Parallax Corporation, a multinational entity that appears to specialize in one very unusual line of work: recruiting and training assassins.

But here’s the disturbing part: these assassins are not professionals in the usual sense. They are “lone gunmen” manufactured by design. Parallax recruits individuals with psychopathic tendencies, sets them up to commit high-profile murders, and then ensures they themselves are eliminated in the aftermath, framed as deranged loners acting on their own. If you’ve ever read about conspiracy theories surrounding JFK, MLK, or RFK, the echoes are intentional.

Frady infiltrates Parallax by pretending to be one of their ideal recruits. The entry point is where psychology enters the story in a big way: he undergoes a series of personality assessments and an infamous film-based test designed to reveal his true nature. The sequences are both fascinating and terrifying.

Personality Testing in Real Life and Fiction

Let’s start with the recruitment test. Frady comes across a Parallax personality inventory, essentially a psychological test battery. Anyone who has applied for jobs in the corporate world will recognize the format. You’ve likely seen those statements on a questionnaire:

“I prefer working alone rather than in groups.”

“I get along well with most people.”

“I follow rules closely.”

You answer on a scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” and somewhere, a computer or psychologist creates a personality profile based on your results and tries to match your profile with an “ideal” worker for the job.

This is not Hollywood invention. Personality testing has long been part of vocational and organizational psychology (Hogan & Hogan, 2001). Employers use tools like the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) or the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) to screen for traits that predict workplace success. Police departments, for example, want officers who are rule-abiding, stress-tolerant, and ethically grounded (Weiss et al., 2013). The U.S. military employs extensive psychological screening, often embedded within broader aptitude tests, to identify recruits’ strengths and vulnerabilities You’ve probably heard of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Although still popular in corporate culture, the MBTI has been criticized by psychologists as more of a “psychological horoscope” than a scientifically reliable instrument (Pittenger, 2005) (we’ll discuss this more in a future post). Still, the desire to classify people into neat boxes remains irresistible to employers and institutions alike.

I’ve been on the receiving end of several of these tests, and they certainly are headache inducing. Related topic, a 20-year police detective who is a good friend of mine recently summed this up as: “They screen out anyone that doesn’t have the same personality flaws, and then they give them guns. That’s a police department”. 😉

Back to the film.

What makes The Parallax View clever is that it flips this logic on its head. Instead of screening out unstable or violent personalities, Parallax Corporation actively seeks them out. Where a daycare would eliminate applicants with psychopathic traits, Parallax wants them at the top of the list.

In the movie, a psychologist character even identifies the test as a tool designed to screen for psychopathy (a personality disorder marked by lack of empathy and violence). This likely alludes to real-world instruments, modern examples of which are thePsychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), which assesses traits like lack of empathy, manipulativeness, impulsivity, and shallow affect (Hare, 1999) and the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI), which is a survey that has been used in both forensic and research contexts to measure psychopathic traits (Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996).

Frady, of course, is not a psychopath. To pass the test, he enlists help from a real one, using their “correct” answers to sneak past the first round. And this sets up one of the most chilling scenes in 1970s cinema.

The Recruitment Film: Subliminal Seduction and the Polygraph Twist

Frady’s second test at Parallax involves being seated in a dark room, hooked up to monitoring equipment, and shown a bizarre audiovisual presentation. At first, the images are comforting: idyllic small-town life, the American flag, family dinners, church gatherings. These are paired with words like “love,” “mother,” and “happiness.”

Then, the sequence shifts. Violent imagery appears: war, riots, sexual orgies, acts of torture. The positive words remain, but now they are paired with disturbing visuals. “Mother” flashes alongside pornography. “Honor” is matched with images of mass slaughter. The tempo quickens. The juxtapositions become jarring and grotesque. All the while, uplifting orchestral music plays in the background, making the scene even more disorienting.

It’s unsettling enough to watch as an audience member today, let alone in the 70s. Imagine being the subject strapped in the chair!

Here’s the psychological brilliance of this scene: it isn’t just a surreal art piece. What’s happening is essentially a physiological screening. Although the movie never explicitly says it, Frady is effectively connected to a polygraph machine. Through sensors in the armrest (and I assume throughout the chair itself….just like in real life…) his heart rate, blood pressure, galvanic skin response (sweaty palms), and micro-movements are all being monitored.

Polygraphs, often sensationalized in film, do not actually detect lies. What they measure are those stress responses (heart rate, breathing, and skin conductance) as proxies for deception or anxiety (Vrij, 2008). In theory, a guilty person feels nervous when lying, and the machine picks up on that. In practice, polygraphs are controversial and considered inadmissible in many courts because nervousness is not the same as dishonesty. Truly, a psychopath may not feel anxiety about lying the way we would, so they may be able to easily beat the polygraph.

But in The Parallax View, the polygraph isn’t looking for truth or lies. Its looking for emotional response, or more appropriately no emotional response. A typical person reacts with discomfort, shame, or anxiety when confronted with disturbing or taboo images. A psychopath, however, would not. Research has consistently shown that psychopathic individuals have blunted emotional responses to fear-inducing stimuli and diminished physiological arousal in such situations (Patrick, Bradley, & Lang, 1993).

So, Parallax’s test isn’t asking Frady questions at all. It is showing him disturbing images and looking to see if he has an anxious response. The reason is, an ideal psychopathic candidate would not flinch (physiologically speaking) at these awful images, but a regular person would. And that’s what the test is doing: it’s silently watching Frady’s body betray him. He may look calm and composed in the scene, but his nervous system is screaming. And the recruiters know instantly that he isn’t one of them.

Lone Gunmen and Conspiracy Thinking

The ending of the film (brace for spoilers) underscores the bleakness of the 1970s mood. Frady is framed as a lone gunman and eliminated. The conspiracy remains intact, the system unchanged. The true monsters, Parallax’s network of manufactured killers, remain hidden, while the public is told that the assassination was just yet another disturbed individual acting alone.

This theme resonates beyond fiction. Think about how many high-profile assassinations or acts of political violence have been attributed to “lone wolves.” The narrative provides closure, but also prevents deeper scrutiny into systemic factors, networks, or broader complicity. The Parallax View takes this idea to the extreme: the “lone gunman” is not just a cover story, it’s a carefully engineered illusion. Pakula’s film was ahead of its time in exploring how institutions manufacture not only killers but also the stories we accept about them. Even The X-Files later nodded to this dynamic, with its shadowy Mr. X character smirking at conspiracy theorists while maintaining the official narrative (when in truth the Cigarette Smoking Man was JFK’s killer!).

Why The Parallax View Still Matters

What makes the movie such a fascinating study for psychologists is how it dramatizes real debates about testing, personality, and emotion. Could a corporation, or a government, identify individuals predisposed to violence and then weaponize them? Frighteningly, are there roles that the government actually wants individuals with little empathy? In an era where algorithms sort us into categories for everything from targeted advertising to security screenings, this question feels less like science fiction and more like actual practice.

The polygraph scene also highlights the limits of control. You can fake answers on a test, but you cannot easily fake your heart rate or your galvanic skin response. Our bodies speak even when we try to silence them. As psychologists continue to develop new tools for lie detection, risk assessment, and personality profiling, The Parallax View serves as a cautionary tale about how those tools might be twisted.

For students, I often frame it this way: films like this remind us that psychology is not just about the clinic or the lab. It is also about power. Who uses psychological knowledge, and for what purpose? Screening out violent tendencies is one thing. Recruiting violence on purpose is quite another. Any brief review of “dark psychology” shows that this is at least being talked about. There’s a reason the APA has an official statement about it being unethical for psychologists to aid in psychological torture of suspects.

Closing Thoughts

If you haven’t seen The Parallax View, I highly recommend it, not just as a thriller, but as a meditation on psychology, politics, and paranoia.

When I show clips (like the recruitment film) to students, I still get uncomfortable watching them, which is the mark of effective filmmaking. The discomfort is the point. We are forced to confront the unsettling possibility that someone, somewhere, might actually want to find the people who are unbothered by scenes of violence, manipulation, and exploitation—and then put them to work.

And that, fifty years later, feels as relevant as ever.

The American Psychological Association’s position barring psychologists from aiding in torture of suspects: https://www.apa.org/about/policy/torture

References

Hare, R. D. (1999). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. Guilford Press.

Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2001). Assessing leadership: A view from the dark side. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1-2), 40–51.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Andrews, B. P. (1996). Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(3), 488–524.

Patrick, C. J., Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1993). Emotion in the criminal psychopath: Startle reflex modulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(1), 82–92.

Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210–221.

Vrij, A. (2008). Detecting Lies and Deceit: Pitfalls and Opportunities. Wiley.

Weiss, D. S., Brunet, A., Best, S. R., et al. (2013). Frequency and severity approaches to indexing exposure to trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for police officers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 734–743.

If the video didn’t work for you, here’s the scene: